Selected Essays

Getting to the Cyclorama: A Brief Personal History

Sanford Wurmfeld

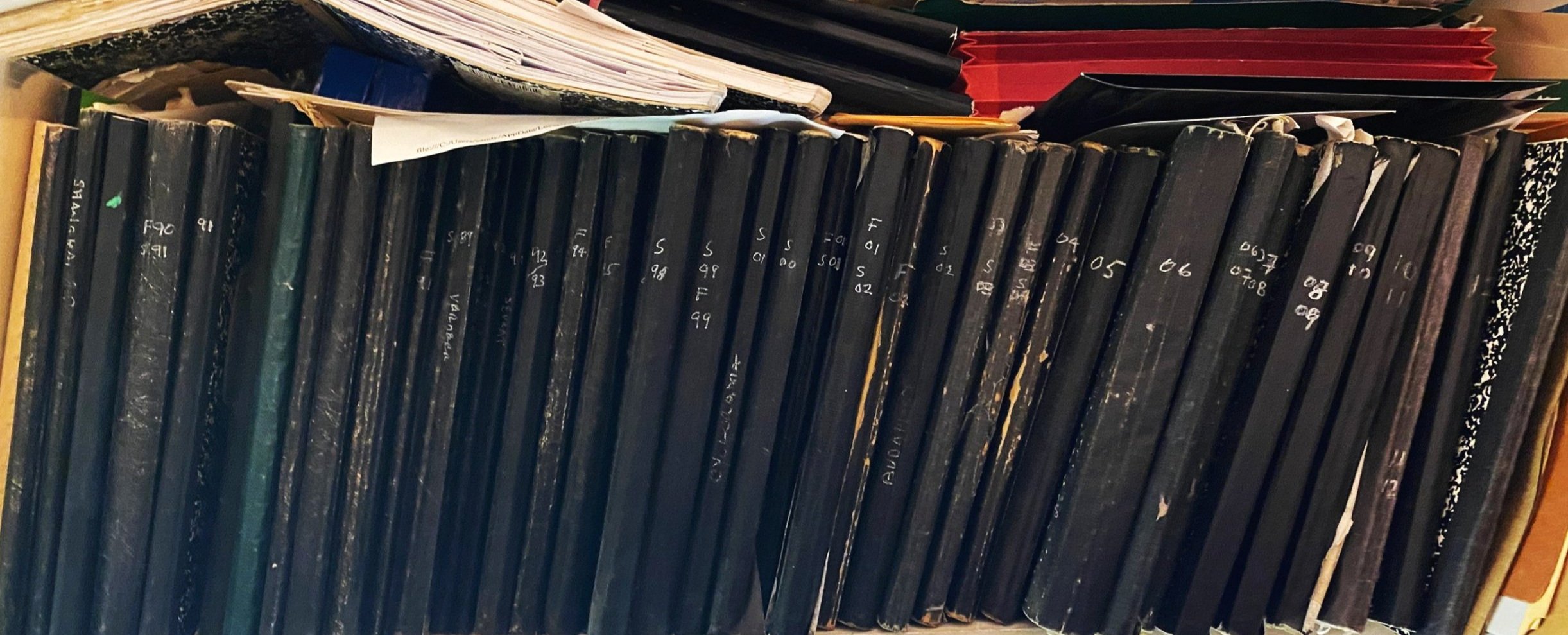

Seeing the cyclorama in relation to my own artistic development, as well as to a broader history of art and especially to site-specific painting will perhaps clarify its significance. My first working venue as a young artist was in Rome, Italy, in 1963. I went to Rome to paint, following my studies at Dartmouth College where I majored in art history and prepared for architectural studies, at the invitation of my brother Michael who was there on a Fulbright grant to study architecture. I was developing abstract art forms, and together with Michael became extremely interested in Roman baroque art - specifically paintings in situ. This started what has become a career-long interest in such art. I traveled extensively in Europe to see and to study, not only renaissance and baroque examples, but also more contemporary integrations of painting and art with architecture. This led to a more primary interest in studying the issue of the use of color in painting. On returning to New York at the end of 1965, I spent a week in the Museum of Modern Art library studying the original edition of Josef Albers' Interaction of Color a book I later acquired as a present from my brother. This proved to be just the beginning of my continuing research into historical and contemporary color theory and the psychophysics of color vision.

My first one person exhibition in the spring of 1968 included the presentation of painted wood columns and clusters of columns (each 15'' wide x 90'' high) meant to be circumambulated to take in the entire experience. These three dimensional "continuous paintings" were based on my evolving ideas about color in art and were intended to relate to the site, but my assumed site was a white room. By shifting to physically transparent materials in 1969, my next group of three-dimensional pieces attempted to deal with the issue of a specific architectural context. These works effectively color-structured space as one walked around them and saw the environment through the color combinations which shifted with each angle of view. The last of these pieces, a color maze made from 21 of these transparent subtractive primary color sheets, was designed in drawings and a small model made in 1970, but was only recently exhibited.

From my earliest attempts in Rome and most specifically since my return to New York in late 1965 my paintings have involved an investigation of color experience in relation to scale and viewing conditions. I pursued this in small scale color studies in order to gain greater understanding of the sensory experience of color in painting. Simultaneously I have attempted to control a presentation of color over an ever widening range of the horizontal visual field. My exhibitions in the 1970s featured paintings that were 6 feet high by 30 feet long. These paintings were meant to structure experiences that reward a searching viewer who is stimulated to attempt a whole range of spatial and temporal visual viewing: from close-up to distant and from short term scanning to long duration fixations. My career-long artistic evolution to extend painting over the broadest possible visual field culminated in a 360 degree panorama which encloses an entire space.

I was inspired to create this first abstract panorama after a tour in Europe with my family during the fall of 1981 when I saw for the first time Mesdag's panorama presentation in The Hague. The work is certainly a tour de force of perspective and stage construction, but even more interesting to me is the extraordinary suspension of awareness of the actual physical space of the room, caused by the simultaneous control of the painting with the architecture and the light - something I remembered experiencing with baroque pieces like Andrea Pozzo's ceiling in San Ignazio, Rome.

Georges Seurat: The Drawings

Exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art, New York

October 28, 2007 - January 7, 2008

Reconstructed Reveries

How extraordinary that a young man working in his early 20s approximately 125 years ago created works of art which continue to fascinate and captivate us today. Though these are clearly representational drawings which are meant to depict subjects, it is the style of the drawings which is unique to Seurat and conveys a transformative visual experience discovered in the act of drawing. Certainly we are not the first to have had this reaction. Some of the best critical minds who have written on art over the last century have reacted similarly and have contributed their insight toward explaining this. Seurat’s contemporary Felix Feneon as well as Roger Fry and Meyer Schapiro later in the 20th century have written of the wonder which Seurat’s work inspired and some clues as to why this was so.[i] William Innes Homer[ii] more specifically took on the task of investigating Seurat’s use of color and his work has been followed with further important contributions by Martin Kemp[iii] and John Gage[iv]. But the greatest contribution to furthering our insight into Seurat’s accomplishments has been by Robert Herbert[v] who focused much of his research on Seurat’s paintings and drawings and then organized not only the large Seurat exhibition and accompanying catalogue at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, in 1991, but also the subsequent Making of La Grand Jatte exhibition and catalogue at the Chicago Art Institute in 2004.

During the time of the Metropolitan’s Seurat exhibition, Herbert organized a symposium of scholars. The morning session opened with Kemp defining and relating to Seuarat’s work the visual color phenomena of optical mixture and simultaneous contrast and then providing a history of the use of these in painting up to the time of Seurat . Gage followed with a recounting of the color science of Seurat’s time and the possible effects of these ideas on his paintings. And Herbert himself ended the morning by emphasizing that though all these ideas were important to Seurat, the artist’s work was nonetheless the result of the discoveries he made in the studio in the process of drawing and painting. These three speakers collectively and cogently outlined the way to enhancing the viewers’ understanding and experiencing of Seurat’s artistic accomplishments.

We are reminded in the catalogue accompanying the recent MOMA exhibition[vi] that Seurat’s drawing technique grows out of the process of his particular kind of mark-making and the quality of the surface of the paper he chose to use. In his writing on Seurat’s drawings, Herbert has traced that “there are three stages observable in this development”, but “this is not necessarily a strictly chronological evolution”[vii] After executing his academic student drawings, Seurat went on to explore a system of “hatching” parallel lines to achieve tonality, as is evident in a number of earlier works such as Seated Woman (c.1880-81). Then in such drawings as Nurse and Child (c.1881-82) this seems to have given way to a rather random all over scribble which varies in density to make the lights and darks. But Seurat’s breakthrough signature drawing style is the one in which he simply uses the bite of the paper to grab the conte crayon in order to create the different tones. The conservator Karl Buchberg details the history of the specific materials and techniques used by Seurat: how this paper was made to acquire the grain which Seurat found so crucial to his technique; the nature and history of the Conte crayon; and the use of fixative and other materials to build layers of tones and to create textures.

What is especially captivating, however, beyond his process of drawing, is the manner in which this technique records for the viewer Seurat’s original way of experiencing things visually. Though Jodi Hauptman, the curator of this wonderful exhibition, perceptively points out in her catalogue introduction that “viewers of Seurat’s works...are always witnesses, never participants”[viii], Seurat must have been a very active viewer himself, and one who consciously became aware of the nature and variety of ways of seeing as he varied his viewing time and distance. The artist then recorded such experiences in his drawings. Thus we come to understand Seurat as a visual investigator of experiences not previously recorded by artists. It was in fact during his lifetime that visual science became a focused field for study by scientists..

Seurat developed his technique to be ideally suited to recreate his vision. Because he varied the pressure and number of passes over the surface texture of the paper with the conte crayon, Seurat created an allover experience progressing from almost untouched and therefore very light through a whole range of greys to very dark, almost black. Seurat made a point of drawing to the edges of the sheet so that the entire surface was part of the intended visual experience. This method - as beautifully exemplified in The Artist’s Mother (c.1882-83) - preceded the subsequent research and analysis of vision by gestalt psychologists who understood the visual field to be composed of “figure and ground” which together form an entire “gestalt”. When we look at this drawing we must conclude that not only had Seurat experienced the visual field as composed of figure and ground, but moreover he composed areas which seem quite ambiguous as to whether they constitute figure or ground - a quality of ambiguousness evident in much later abstract art of the twentieth century.

Another of Seurat’s visual discoveries was a sense of “film color”, though this is a term first coined much later by the Gestalt psychologist David Katz in his 1911 volume on color[ix]. Katz is appreciated for distinguishing various “modes of appearance” of color, but his main distinction is to have explained the difference between surface color and film color. He defined the surface mode of appearance as color seen attached to a surface or object and therefore spatially located, while to Katz the film mode is defined as the appearance of color seen as if detached from any object or surface as though floating in an indeterminate space. It is extraordinary that Seurat, having seemingly understood this mode of color appearance, attempted to recreate his impression of this film color experience by presenting a not quite fused optical mixture of elements together with a generally “out of focus” edge condition for his subjects. These drawing choices result in both the “atmospheric” quality in Seurat’s drawings and the sense that objects are seemingly floating in an indeterminate space. Looking at his drawing Horseman on a Road (c.1883) confirms this. The active viewer can further appreciate Seurat’s investigation by viewing the drawing from 15 to 18 feet away (admittedly very difficult in the context of a crowded museum). By doing this, the viewer tends to have a more in focus experience of elements which would otherwise appear difficult to make out at a closer viewing distance.

Seurat even depicted yet another experience of film color. This is seen in his use of what some have called “irradiation” effects (seemingly derived from David Sutter’s use of the term[x]) or “lustre” (used by Homer and derived from Ogden Rood’s[xi] elaboration on the term, which he stated he derived from Dove, a 19th century visual psychologist). The meaning of the different terms gets confusing, especially in relation to contemporary uses of the words lustre and irradiation. What is implied by the terms lustre and irradiation when referring to Seurat’s drawing is actually “simultaneous contrast”[xii]. One’s experience of either an afterimage or simultaneous contrast provides a film color experience. Since both phenomena occur in the eye/brain system, the enhanced contrast color or complementary color move as one’s gaze wanders, and so it neither feels as if the color is attached to any object nor is it located in any particular space. It is evident that Seurat has drawn his impression of this longer durational viewing experience necessary for simultaneous contrast to happen, by heightening the contrast where light meets dark. Many good examples of his single figure drawings exhibit this effect, for example The White Coat (Woman with Umbrella) (c.1883) or the two figures seen together as a single group in Nurse (c.1882-83).

Seurat’s choice to offer different examples in his drawings of his experience of the phenomenon of simultaneous contrast reveals the variety of his visual investigation. We know that this phenomenon occurs only after a period of fixation in the fovea, which is the very central area of vision, but it does not occur across the entire visual field all at once. If a few elements are seen from a sufficient distance that they are seen within the fovea, then one might see simultaneous contrast effects around a number of figures or elements. In drawings of multiple figures such as Man Waiting on a Sidewalk (c.1884-86) and The Couple (At Dusk)(c.1882-83), Seurat showed us which particular figure he was fixating on by rendering simultaneous contrast enhancement around that particular figure only, while the fleeting figures in the apparent distance are rendered without such contrast enhancement. But what can we make of later drawings of multiple figures where the fovea of the eye could not possibly have encompassed the entire field rendered, and yet we see depicted contrast enhancement around most if not all the elements? This can be seen in Café Singer(c.1887-88), Eden Concert(c.1886-87), Two Clowns(c.1886-88), and Pierrot and Colombine(c.1887-88) wherein each element in each drawing shows the effects of contrast enhancement. If in fact Seurat was not viewing his compositions in these instances from a great enough distance to record only what he saw in the center of vision, then he has recorded something else - a series of fixations as he evidently did in many of his paintings and especially in his late marine paintings of Graveline. As he scanned and then fixated on each part of the visual field before him to experience the simultaneous contrast around each element, he was able to describe an almost pre-cinematic experience of vision - alternating scanning with fixation.

Rather than having simply drawn a simple figure with unmodulated tones and focused edges to allow the viewer to have a similar durational experience of simultaneous contrast, Seurat chose to describe for us what were for him new experiences. Seurat thus expressed in his work the idea of psycho-physical time as being inherent to the very nature of our experience. The subject of time had been expressed in art prior to Seurat as part of the narrative subject of a work, for example, in works which record moments in history, sequences of events in history, or times of the day or the seasons. Seurat, however, seems to have been trying to describe something else: the subjective time of one’s actual viewing experience as a constantly changing factor of one’s construction of reality.

Interestingly, psycho-physical time was simultaneously being investigated in a number of other fields. Seurat was born in the same year as the Frenchman Henri Bergson, who along with others explored philosophically the notion of time and duration in experience. Seurat was active at the time Ernst Mach first published his Analysis of Sensations (1886) and other psycho-physicists in Germany were pioneering research in sensation and perception which involved durational effects. During this time government organizations were meeting to create time zones and eventually to standardize world time. Moreover, when Seurat was in his maturity in the 1880s, E.J. Marey was also in France creating “chronophotography” and Le Prince was there developing an early camera-projector. So the notion of time - both in its physical and psycho-physical dimensions - was very much a subject of that era in several fields.

Seurat’s unique style thus achieved three important results: 1) he created from bits of dark on the light paper an over all sense of a not completely blended optical mixture (parallel to his use of dabs of paint on canvas), which allowed him to control focus and thus add to one’s sense of film color; 2) he created a sense of an entire visual field constructed by figure and ground with sometimes ambiguous readings; 3) he was able to vary lights and darks to render the effect of simultaneous contrast resulting from viewing duration, to further create a film color experience. These results, in effect, allowed Seurat to reconstruct for the viewer the reveries of his own visual explorations as he wandered the environs of Paris. Rarely in the history of art has an artist combined his working process to express so clearly the very nature of his being and the spirit of his time with such direct economical means as this young man, Georges Seurat, achieved in such a short career.

[i]see selections in Norma Broude (ed.), Seurat in Perspective, Prentice Hall, NJ, 1978.

[ii]William Innes Homer, Seurat and the Science of Painting, M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, MA, 1964.

[iii]Martin Kemp, The Science of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 1990.

[iv]John Gage, Colour and Culture, Thames and Hudson, 1993; Color and Meaning, University of California Press, 1999; Color in Art, Thames and Hudson, 2006.

[v]Robert Herbert, Georges Seurat, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1991; Seurat and the Making of La Grande Jatte, The Art Institute of Chicago, 2004; Seurat Drawings and Paintings, Yale University Press, 2001.

[vi]Jodi Hauptman, Georges Seurat-The Drawings, with essays by Karl Buchberg, Hubert Damisch, Bridget Riley, Richard Shiff, and Richard Thomson, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2007.

[vii]op. cit. 1, p 125.

[viii]ibid, p14.

[ix]David Katz, Die Erscheinungsweisen der Farben und ihre Bezinflussung durch die individuelle Erfahrung, 1911 (First German Edition); Der Aufbau der Farwelt, 1930 (Second German Edition); The World of Colour, translated by R. B. MacLeod and C. W. Fox, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd, 1935, (based on the second German edition).

[x]David Sutter, Les Phenomenes de la vision, 1880.

[xi]Ogden N. Rood, Modern Chromatics, D. Appleton and Co., New York, 1979.

[xii]clearly defined for artists by M.E.Chevreul, De La Loi Du Contraste Simultane Des Couleurs, Paris, 1839.